Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Through half a dozen novels I’ve read since 2014, Furst has never disappointed. In a deceptively quiet voice he portrays the complexity of life in situations too often cartooned as ‘dramatic’, ‘heroic,’ or ‘epic.’ Heroes are not sprung from the loins of goddesses, he shows us, but grown from the soil of ordinariness, seeded by terrible circumstances, watered by relationships with other decent human beings and nourished by the force of life itself as they seek the paths which will allow them to go on for another day, a week or if they are very lucky, even longer.

For Red Gold, we travel in the company of one Jean Casson, a Parisian film producer trying to survive under the Nazi occupation. Having once been picked up by German intelligence and escaped their clutches, he must now hide in plain sight, growing a mustache and dressing poorly as he adopts a false in hopes of not being recognized contacts from his old life. Learning to watch in every direction at every moment Casson, who is himself no socialist, drifts into contact with Communist resistance fighters, directed and bankrolled by the Soviet Union. They in turn find his character and connections useful, loosely employing him as liaison to other factions – free French disruptors, conflicted Vichy collaborators and anti-Communist nationalists partially directed and intermittently supported by the Allies’ military for their own ends. All of these, and also the Nazis, of course, are quite willing to sacrifice any individual at any time, if it serves their particular ‘greater purpose.’

As always, Furst paints a convincing and absorbing picture of life under occupation: the drabness, the cold, shortages and unexpected moments of plenty. Casson’s inner voice is witty enough to entertain and resourceful enough to keep him and the reader out of the worst trouble, at the same time he manages to find enough minimalist romance to leaven the despair. These characters have no foreknowledge of how the war will turn out; at any moment this depressing moment in history may take their life and so define it – a tragedy deeper and more painful than the destructive result of any brilliant explosion or dramatic car chase.

Life goes on, even under the heavy hand of war, and as much as some persons may fight for glory or principle, what most really want is simply to keep on living, with perhaps a bit of food, a sip of drink, a smoke or a hint of love to make it worth the effort.

Definitely an author to return to, and with around fifteen novels focused on the war years in Europe (published between 1988 and 2019 and collectively referred to as ‘The Night Soldiers series’) there’s plenty of opportunity to keep Alan Furst on the shelf.

(Note: Furst’s The World at Night (1996) shares a common plot and protagonist with Red Gold, so other readers may benefit from reading that volume first. His three earliest novels, published in ’76, ’80 and ’81, concern drugs and crime in the U. S. I’ve not sampled them but hope one day to do so).

My own latest novel is currently being serialized on this site. You can read the first installment in the recent post titled E Unum Pluribus.

If you like what you read here at robinandrew.net, please share any posts as widely as possible, and consider subscribing – it’s totally free!

Wondering where our nation’s increasingly divisive politics may lead us? E Unum Pluribus is a new novel which explores one very real possibility:

Amid feudal chaos following the USA’s collapse, one city-state seems promising, until an amateur’s murder investigation exposes its weaknesses and the conspiracies threatening to destroy it.

In order to receive community input, I’m serializing a Beta Test draft of E Unum Pluribus free of charge. (So I can track interest, the final installment may be posted only to subscribers, but even that subscription will be totally free of charge or obligation.) A .pdf of Installment One is included below and may also be downloaded for a more comfortable reading experience. Either way, you get to explore this new novel at absolutely no expense!

Succeeding installments are available at robinandrew.net by selecting the ‘E Unum Pluribus’ button in the home page’s top-menu.

In addition to posting the manuscript, I will be sharing thoughts about the novel’s themes and objectives in future posts on both this website and on Substack at nobodysays2025.substack.com

If you find E Unum Pluribus of interest – or if you simply support the concept of authors sharing their work without reliance upon commercial publishing corporations – please share this post as widely as possible.

Have a wonderful 2026!

Robin Andrew

By now many observers have noted Mr. Trump’s tendency to accuse his detractors of whatever sin he himself is engaged in. Those observations suggest some thoughts around the Great Replacement Theory which, in Trumpian usage, holds that Democrats are intentionally perverting democracy by opening our sacred borders to untold millions of immigrants (who just coincidentally tend to be black, brown and/or from ‘shithole’ countries not part of the Anglo-European heritage which we are now being told defines true Americans).

Thought number one: acknowledging that Mr. Trump won the election in 2024 and so is legitimately occupying the Oval Office, he still received fewer than half the votes cast,* an inconvenient truth which makes one wonder if perhaps there is a hidden thread connecting several of his administration’s current priorities.

To whit: contrary to the populist image their leader loves to act out, he and any thoughtful members of his court must be aware that theirs is a minority faction and so will never be able to hold power by democratic means. Unable even to rely upon their slender majorities in Congress to do their bidding, they know they cannot govern by legislation (as the Constitution intends) but must rely almost exclusively on Executive Orders, Presidential Determinations, Proclamations, administrative directives by their chosen technocrats, petty prosecutions and the like – despite the dubious validity or effectiveness of many such.

Second, since he and they are unwilling to adjust their policies to the beliefs of the voting majority, they choose instead to speak and act as if the voting majority itself is invalid, tilted toward ‘radical’ outcomes by the presence of millions of non-citizen immigrants. If – goes the fantasy they imply to their base – the administration can eliminate enough of those ‘illegals’ through holding-camps, deportation, self-deportation, remigration or whatever other terms they come up with next, then the voters who are left will constitute their dream of a majority MAGA electorate. That hope energizes their base and recruits enforcers for ICE and other agencies, but unfortunately for MAGA, their inability to produce any credible evidence of voting by non-citizens in numbers that would make any difference in any election at any level demonstrates the fallacy of such hope. Illegal immigrants have never swung actual voting so even their complete extermination would not affect any future outcome. The pro-Trump minority is not democratically viable* and his power can only be ensured by non-democratic means.

Which explains the Administration’s doubling-down on tactics to frustrate the democratic will. Demands for state gerrymandering, discouragingly cumbersome voter ID requirements, restrictions on drop-boxes, voting locations, hours or mail-in options, false accusations of voting machine irregularities, placement of threatening ‘monitors’ at election sites, these and many other strategies are designed to deter enough voters to ensure MAGA victories whether or not the majority of eligible voters want them or, in the worst case, to provide excuses to override the true verdict when it proves they do not.

One can even interpret MAGA’s recent call for Americans to have more children as a supply side complement to these strategies. Refuse to naturalize any but the wealthy and pale at the same time the MAGA faithful produce more and more purebred American babies (who will, presumably, be groomed by their parents to vote the ruling party’s ticket from birth) and they might just turn their minority into a real majority – in twenty or thirty years.

All this can be seen as one more indication we’re lost on a dark and very slippery slope or, looked at from another angle, it may give a sliver of hope. Since the people he is tossing out the door were never part of the majority who voted against him, Mr. Trump’s epic cleansing will do nothing to change his minority status. In fact, if the callousness and brutality of it repels even a few of his past followers, it will actually drive his share of future vote tallies lower. In which case, the majority of the American electorate may one day reject Mr. Trump’s imperium by a large enough margin that not even doomed third-party candidates and the misrepresentative calculus of the Electoral College will be enough to save him.

Here’s hoping that whenever that day comes, there is still a nation left to rebuild!

*Of the three elections in which Donald J. Trump has ever competed, he has never won a majority of the votes cast. If that is any sort of mandate, it is a mandate against Mr. Trump, not for him. The fact that he was elected in 2016 reflected just how unsuited our present Electoral College structure is to today’s electorate, in which the population disparity between large states and small ones is more than five times as wide as it was at the time the Constitution was being developed, yet each of those states still gets an equal two Senate-related votes. The fact he was elected in 2024 despite not winning a majority is its own indictment of an election process held captive to two ossified major parties which cannot possibly represent the true diversity of their electorate.

Like this post? Feel free to share it.

Appreciate what you read here, please subscribe – it’s free!

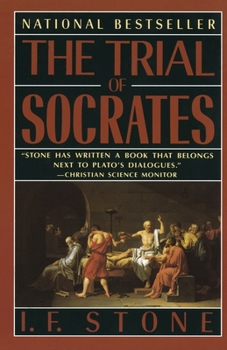

Isidor Feinstein Stone was widely known and read as a liberal/socialist leaning journalist and newsletter writer from the 1930’s to the ‘80’s. His introduction to the paperback edition of this book suggests it was the product of a late in life desire to move away from investigating current injustices and stake a claim to something timeless.

In that, Stone acquits himself admirably, analyzing the works of Plato, Aristotle, Euripides, Xenophon and others like a professor of the Classics, along the way citing a wealth of references both primary and secondary, some of which seem quite obscure. His commentary on specific words of Ancient Greek – their origins and multiple usages and especially the implications of how they’ve been translated (or mistranslated) over the ages – suggests an ability to read the original Greek language sources, which is impressive in one whose Wikipedia entry records only that he dropped out of the University of Pennsylvania

Greatest take away for this unschooled reader is to reframe Socrates from a revered name in the pantheon of Athens’ great philosophers into a rather disreputable rascal; a gadfly and rabble-rouser accused of corrupting the state’s youth by arguing the efficacy of oligarchic tyranny at a moment when such evils had very recently taken advantage of democracy’s natural disorder to seize power for themselves – twice! – and stood eager to do so again at any time. Also, as Stone puts it, a man who habitually and resolutely argued the negative side of every issue without ever offering a single positive value to which he would actually commit. This, in Stone’s view, is the real reason Socrates seemed to actively seek and welcome his death sentence (at an age when he could otherwise look forward only to sickness and decline) and turned his own death into a performance calculated to seal his place in posterity. As likely as it was that a defense on the grounds of free speech might have saved his life (the last chapters of the book analyze this in extravagant detail), Socrates would not demean himself by pleading a principle against which he had previously argued with all his eloquence. Even more, he seemed purposely to alienate his judges so as to be sure they would not honor their own and their City’s principles by freeing him on those same grounds.

Which last leads into the second lesson of this author’s analysis. An ardent supporter himself of the right to speak freely, Stone reminds the reader that such a right has very rarely been the policy of any government or governing system. Even among the Golden Age Greeks it was a niche freedom, always tempered by its applicability only to those accredited for a specific body or forum, or only those of wealth and privilege, only those meeting citizenship requirements, only those owning property, only those not owned as slaves or reviled as foreigners or uncivilized – the list goes on. That freedom of speech was not a universal value even among those greats in that great time and place is a very valuable reminder for those of us living in this one (U.S. A, 2025)

Certainly worthwhile to read and know, Stone’s analytics in The Trial of Socrates feel repetitive and over-argued; one imagines the same points could have been made in an essay rather than a book. But then, an essay about such a scholarly subject would never have achieved the visibility and stickiness this stand-alone book has (much less been deemed a ‘NATIONAL BESTSELLER’ as the paperback jacket proudly proclaims). Pulling Socrates off his pedestal at the same time it raises the U. S. First Amendment’s guarantee of Free Speech up onto one of its own is pretty good work for a small volume (247 pages plus Notes) by the college-dropout son of an immigrant shop owner? Achievements well worthy of a space on the shelf.

Following up recent rereading’s of Orwell’s 1984 and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 I saw this speculative novel recommended for its prescience and found that characterization to be spot on. Writing back in 1993, Butler describes a Southern California that could believably result from just a few more years pursuit of our nation’s current course. Widespread poverty thanks to an politicians who own power over actual governance, violence and destruction by a populace fragmented and distrustful of one another, worldwide ecological disasters, misuse of new technology for profit and oppression, legal and police powers used not to protect the rights of all but to entrench the power of the few and, overlaying all that, a portion of the populace turning to reactionary religious movements in hope of refuge. A decidedly dystopian take on our situation, but very convincing and valuable as an eye-opener. That it is set in our exact time (July 2024 – October 2027) despite having been written over thirty years before is almost spooky to one first reading it today.

Butler (born 1947, died 2006) was a pioneer: at a time when it was striking to find either a Black person or a female making a name writing science fiction she was both, going on to win Hugo, Locus and Nebula awards as well as a MacArthur Fellowship grant. This first of her works that I have read (there will be more) is partly shaped by her ethnicity, featuring a mixed race band of refugees and touching repeatedly on how race has shaped them, has affected their fortunes and is still affecting them despite the near total collapse of nearly every other social structure.

Not content to cover that weighty ground, Butler also puts forth a religious theme, with protagonist Lauren Oya Olamina (which surname we learn is from the Yoruba region of Nigeria) the daughter of an Evangelical preacher. Lauren is in the process of devising a faith of her own, which she calls Earthseed in reflection of its vision of destiny – the expansion of Earth’s humanity to live among the stars and spread their ‘ seed’ throughout the universe. Lauren’s coming to grips with that calling and beginning the process of dissemination is the true theme of the novel, all the others serve to set the conditions and inform the necessity of her doing so.

Butler’s writing is immediate and colorful yet quick and concise, her plotting is complex without falling into the sort of techno traps that affect much Sci-fi. Resultingly, the Parable of the Sower is a work of literature which uses its genre as vehicle, not a commercial work safely exploiting a comfortable niche. A sequel, Parable of the Talents (1998) presents a further step in Laruen’s and Earthseed’s journey, culminating in departure of their first space craft on a colonizing mission. That having been Butler’s final published novel, it is sad to consider how she might have continued the tale, had she not struggled with depression and writer’s block before passing away in 2006, at the too-young age of 58.

Very glad to have encountered both book and author, and highly recommend them to any readers interested in where our politics are leading the USA, exploring the canon of science fiction, alternatives to mainstream religion or just curious about where human society may be headed – in both the near and the far terms.

Saw an excellent opinion piece recently about the history of Amendments to the U. S. Constitution, starting with the fact that the document’s authors fully intended it to be revised – the Amendment process is written in, after all (Article V) – and running up through our fifty-plus-year drought of amendments since the 1970’s. It can certainly be argued whether our current divisiveness and the dysfunctionality of Congress are one reason we’ve had no Amendments recently, or one result of that, but the phenomena are certainly related to one another.

Well-thought-through and widely-accepted new Amendments could allow our nation’s founding document to grow and adapt to conditions which have changed dramatically, including: a population which has gone from about four million peeps in 1790 to some 330 million in 2020; a mix of states which has gone from 13 small, young and rural ones to 50 with wildly varied histories, populations and urban/rural characters; multiple technological and cultural revolutions; and an international context the Founders might well struggle to recognize.

Given all that, here are a few modest proposals to be considered when the time seems right

Free the Courts: we’ve all been taught that the Federal government has three branches -the Legislative, the Executive and the Judicial (perhaps equal, perhaps not, depending…) and that this configuration ensures checks and balances on the power of each, thereby protecting the system and our freedoms. Current events are making clear that the Judicial branch is not really an effective check or balance so long as the Chief Executive appoints (even with Legislative approval required) and can fire (at will and whim) the Attorney General, thus allowing that Executive to direct and weild the enormous power of the Department of Justice as he or she wishes. A new Constitutional Convention, or a renewed and less-rigidly divided and more collaborative Congress would do well to consider an Amendment to remedy this by making Justice independent of the Executive branch and the Attorney General an elected office with a four year term, perhaps voted upon in Presidential off-years, and no longer a member of the President’s Cabinet (though still with other rights and privileges of Cabinet level responsibility and authority).

While we’re at it: how about also solidifying the makeup of the Supreme Court by fixing it’s number (rather than leaving it vulnerable to change by some future legislature) and specifying a limited term for justices (so the Court better reflects gradual changes in society and culture) with staggered start dates (so no one President/term gets to appoint more justices than another (whether by random happenstance or by McConnel-esque abuses of Congress’s approval authority). Those changes would work against the politicization some believe we are experiencing with the current Court. And, since we’re talking pie in the sky, maybe even consider requiring each Justice as they take their seat to designate a successor who will fill out the rest of their term should they die, be incapacitated or simply exhausted before it runs out (thus avoiding any lucky President – or violent actor – taking advantage of such an event to pack the court with their preferred jurists).

Speaking of elections: one aggravator of our recent discord has been the ascent of Presidents to office without receiving even the barest majority of the votes cast (not to mention those who did not even receive a plurality!). More than just casting doubt upon a leader’s legitimacy, this has led too many citizens to conclude that their votes are not worth casting. A constitutionally-mandated two-stage election would address this issue, with as many candidates/parties running in the first stage as wish to and then just the two top vote getters participating in a run-off election to decide who will hold the office. That format would ensure the winner receives a majority of votes, while also offering an unmistakable indicator of just how strong or weak is their mandate. It might also diminish the stranglehold of two-party politics, since a third-party or independent candidate need only defeat one of the two major parties to reach the runoff (and have a legitimate chance at the White House), rather than having to surpass both of them from a standing start as under the current system. Whatever expense or delay is incurred by this two-stage process might have ruled it out back in the founders’ days of carriage rides and snail mail but would be entirely manageable in today’s electronic age.

(Debating and reaching agreement on issues like those might even serve as a warm-up so said Congress or Convention could address the stalemate between small and large states with an amendment that retires or at least updates the Electoral College so Presidential Elections would more fairly deal with the enormous disparities in populations relative to Senatorial votes.)

Obviously, tons of other ideas for amendment are out there and more will quickly arise if the ball ever gets rolling, but those above seem to this writer to be top of the list. The time is ripe for us to use the tool those wise heads passed down to us in order that their legacy may be improved and sustained for many more generations!

P. S. – This post was inspired in part by “Amend It!” written by Jill Lepore and appearing in the print and online editions of The Atlantic, October 2025. Neither M. Lepore nor The Atlantic have any connection to this post or site, nor are either in any way responsible for its content.

If you find this post of interest,

please feel free to share it with others.

If you like what you find here at robinandrew.net,

please subscribe – it’s free!

Like a 75-year-old car, Bradbury’s most lauded novel feels a bit clunky compared to the sleek and smooth commodity fiction churned out by today’s industrial publishing conglomerates. As with any mode of transportation though, where a book takes you is more important than the vehicle itself, and Fahrenheit 451 offers a ride through the very territory over which our nation is currently circling. Pretty amazing for a story first anthologized in 1950 and expanded into this short novel in 1953!

Minds colonized by omnipresent ‘entertainment’ media pretending to provide viewers with a ‘reality’ more acceptable than their own; lives lived in bubbles of class and clique; an authoritarian government ginning up perpetual wars as excuse to police every facet of its citizen’s lives; new technologies immediately harnessed to enforce all of the above – Bradbury’s fears for his characters’ ‘future’ are amazingly close to today’s realities.

In an afterword and coda written later (1982 and 1979, respectively), Bradbury makes clear that he traces all those developments to his fictional culture’s rejection of the written word. Books there are viewed as corrupting distractions. Not content with discouraging or banning individual volumes on the basis of specific content, this regime fears all books because they record, preserve and encourage independent thought. The very possession of any book has been declared a major criminal act and the once laudable community symbol of the Firefighter has been perverted into a new role as government book burner (and incidental executioner of bibliophiles).

So here we are seventy-five years later, with citizens pressuring their libraries and schools to dispose of any books hinting at truths those particular citizens don’t appreciate; a juvenile Secretary of ‘War’ decreeing which slanted versions of history, philosophy and the social sciences may be read or discussed in the military’s colleges and academies as the White House extorts even private universities to teach to the President’s personal prejudices. Meanwhile, surveys confirm that fewer and fewer and fewer persons are reading any books by choice, preferring instead to have information spoon-fed into their brains via profit-tailored algorithms curating content for their profit-driven mass electronica. In spooky parallel to Bradbury’s Firemen cum Fire-setters, the current administration has given control of many federal agencies to fanatical minions who despise those agencies’ statutory functions, wishing instead to destroy or pervert them by flipping them from protecting the environment or civil rights, for example, to opening the former to plunder by political contributors and restricting the latter’s protections to only those who bow down to the MAGA movement in all its glory and gory ambition (while sporting an appearance that comports to Mr. Trump’s old-Hollywood vision of how true Americans are supposed to look).

Despite some age-appropriate road wear and rust in its wheel-wells, Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 is no junker, but a precious classic vehicle for waking up the masses, every bit as timely today as when its rubber first hit the road. It deserves to be read or reread as widely as possible, so more citizens will see what is happening and do what they can to stop it.

P. S. – Along with Orwell’s 1984, and Animal Farm, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, Huxley’s Brave New World, Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange and others from the mid-Twentieth, this novel has helped to shape the fears and ideals of multiple generations. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower are notable among many other recent and creditable volumes with similar aspirations of enlightenment and warning. Now more than ever, all such books deserve to be read and shared.

Like this book or this post? Please Share it!

Interested in what you read on this site – please subscribe. It’s free!

According to reports*, Elon Musk’s new AI-generated online encyclopedia, Grokipedia, begins its entry for gender with: “Gender refers to the binary classification of humans as male or female based on biological sex…”

Wrong! Gender and sex are not the same things!

That Grok thinks they are**, indicates it has been ‘taught’ to parrot the opinions of its human creators. Like a young child, it is not worldly or intelligent enough to think beyond what it has been told by its groomers and so sees the world through their blinders.

For AI as with any other computative system, the value of output is highly dependent upon the quality of input. The first law of computer science – ‘garbage in, garbage out’ – is worth keeping in mind as AI’s very human procreators inject their offspring into as many facets of our lives and world as they can, as quickly as possible, with no oversight and often without our consent or even our awareness.

Knowledge is power, and ignorance posing as intelligence is an abuse of power, not a sign of the glorious and unadulterated progress which AI’s promoters claim to be offering to the world.

CAVEAT UTILITOR!

If you like this post, feel free to share it.

* This post refers to a report by Will Oremus and Faiz Siddiqui in the electronic edition of the Washington Post on 2025-10-27 titled “Elon Musk launches a Wikipedia rival that extols his own ‘vision’”

** In case there’s any question: ‘Male’ and ‘female’ are classifications of sex, which is about biology and can mean, depending on who is speaking, which chromosomes a person’s cells carry, which type of reproductive cells their body produces, which genitalia it exhibits, etc. ‘Man’ and ‘woman’ can refer to various selections from a wide range of public behaviors, perceptions, expectations and putative rules which are loosely and collectively referred to as gender. Sex and gender terms are sometimes congruent, sometimes not, but they are not the same things, as Grok seems to believe.

If you like what you see on this site,

please subscribe.

It’s absolutely free!

Reliably kind and astute, Strout is a treasure, mining small town Maine for evidence of the human condition; what it takes to survive childhood, adulting, family, romance, loss and the passage of time.

In this installment, we are reunited with aging versions of Lucy Barton, Olive Kitteridge and other characters from earlier Strout novels as they continue the messy business of life. The tale is structured around an unlikely relationship between Lucy, the oddball outsider and Olive, the life-long local and gossip coming to grips with the shrinking world of retired widowhood.

The stories Olive tells to Lucy (and others we glean along the way) eventually coalesce around one theme – they are all about secrets. Bits of information perhaps insignificant, perhaps life-changing, which characters have kept from spouses, siblings, neighbors and often, sometimes for very long times, from themselves.

Partway through what seems a familiar journey, Strout drops in a murder mystery, something readers of her earlier novels may find incongruous, even disconcerting. That sort of drama is not her usual cup of tea. Characteristically though, the mystery develops gently and organically, out of seemingly small bits of character and behavior. For a time, it even seems to have drifted from the author’s attention, then is brought back into focus by other events before being solved well short of the novel’s end. Rather than the book’s raison d’être, then, we understand even murder as one more instance of secrets kept, or not. More dramatic than most, but the same animal underneath its skin of violence.

Thus the title, Tell Me Everything, is really a misdirection: No healthy happy person actually tells ‘everything.’ And, if one does try to do so, they’d best be prepared for serious consequences. Sometimes, the path most conducive to happiness, the path of love and caring, may actually lead through the difficult decision to not tell everything, but to live with our secrets and let others live without having to confront them.

Simple insight on a complex reality. Sad and humorous, depressing and reassuring, life changing, life affirming, unremarkable and unavoidable and – in the right hands – captivating and moving.

Another gem from the lapidary mind of Elizabeth Strout. May she live and write forever.