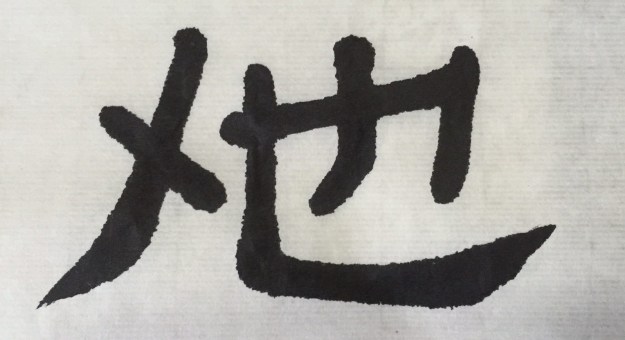

John McWhorter published an Opinion piece recently* about the evolution of pronouns, with particular attention to a new character gaining attention among users of the Mandarin language (X也, shown in image above, combines features of the characters for both he and she, rather as some persons do). Along similar lines, a new novel, E Unum Pluribus, speculates a future American city/state called Confluence in which government edict directs all official communications to employ non-gendered pronouns. The novel’s events make clear that Confluence’s government has plenty of faults and weaknesses, but this one of its policies merits some consideration.

For generations the convention in English was to use ‘he/him/his’ as default and inclusive of all, regardless of their sex/gender. Appropriately, that has now been perceived as favoring male identity over female; simultaneously reflecting historic inequality and perpetuating it. Replacing all those instances with ‘he or she,’ ‘his or her,’ etc. is hardly workable, especially in spoken communications, and still carries a hint of misogyny by placing one gender ahead of the other, whereas ‘she/he’ risks offending insecurities on the other side of the identity coin.

Recent efforts to innovate ‘they’ as a singular pronoun for persons who choose to declare themselves non-binary run aground first on its pre-existing function as plural, generating confusion where they intend clarity. That usage also seems to open the door to a trickle of additional new pronouns as various groups or orientations demand similar recognition; one need only read the snarky online critiques of how LGBT has grown to LBGTQIA2S+ to know that is not a path to tolerance so much as a guarantee of further friction. Worst, in this opinion, ‘they’ singular requires persons who prefer not to be stereotyped as either ‘he’ or ‘she’ to state that publicly, thereby outing themselves and very possibly inviting prejudice, at least at this point in our societal evolution.

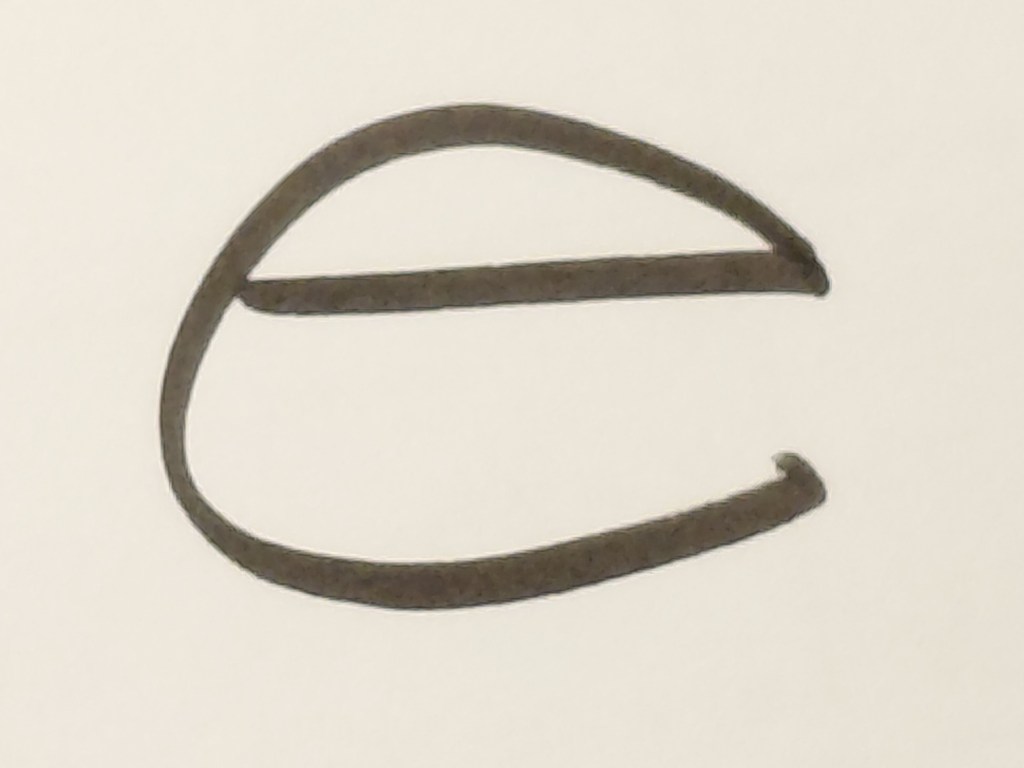

The fictional founders of Confluence have taken another approach; directing official communications to use ‘e/em/eir’ for all individuals. This treats everyone with equal respect and does not require the clunky ‘my pronouns are…’ , which can itself incite prejudices. The specific form, ‘e,” ‘em,’ and ‘eir’ are brief and efficient, similar enough to other pronouns that they quickly feel familiar but with sufficient difference to avoid confusion**.

By applying equally to all possible personal preferences ‘e’ equalizes all in one swoop while tacitly expressing the truth that for virtually all public or official interactions there is no proper reason to indicate what genitalia an individual bears or with whom they choose to become intimate. Those are – and should remain – irrelevant.

There’s nothing revolutionary here, by the way, modern English already has gender neutral pronouns – ‘they’ does not presume the gender of a group or any of its individuals. ‘It’ can be used for all objects – unlike French, say in which some nouns require feminine constructions and other nouns masculine, despite the objects having no actual sexual function or accoutrements. Most prominently, ‘I’ is the same for any individual regardless of sex, gender or other characteristic. It is really only in the second person singular that our language’s evolution has codified an unfortunate and outdated discrimination.

In the world of E Unum Pluribus, that governmental edict for official communications also does not mean ‘e’ is used by everyone all the time. Non-official conversations use gendered pronouns wherever a subject’s preference has become clear, sticking to gender-neutral when an individual’ presentation is itself gender neutral. As in real life, casual usage and common courtesy have the final word in how language evolves over time.

(For what it’s worth, future posts on this site may selectively incorporate ‘e/em’eir’ pronouns to explore just how functional they are – or are not.)

*“This Novel Word Speaks Volumes About How an Entire Language Works” N. Y. Times online edition, 2026-01-22

** E Unum Pluribus does not claim to have invented the ‘e/em/eir’ construct. Variations on what are sometimes called ‘Spivak pronouns’ have been noted at least as far back as the late 19th-century.

P. S.: E Unum Pluribus is a tale of murder and conspiracy set a decade or so in our future in one of many small sovereignties sprung up in wake of the USA’s self-destruction. The novel explores multiple themes – language and gender, identity, guilt and even the origins of faith and belief – but speaks loudest in its depiction of how much we all stand to lose if we continue to retreat into factions which each act only for their own needs and interests.

The manuscript is available in six instalments, starting at:

If you like what you read here or at robinandrew.net, please share any posts as widely as possible – and consider subscribing: it’s totally free!