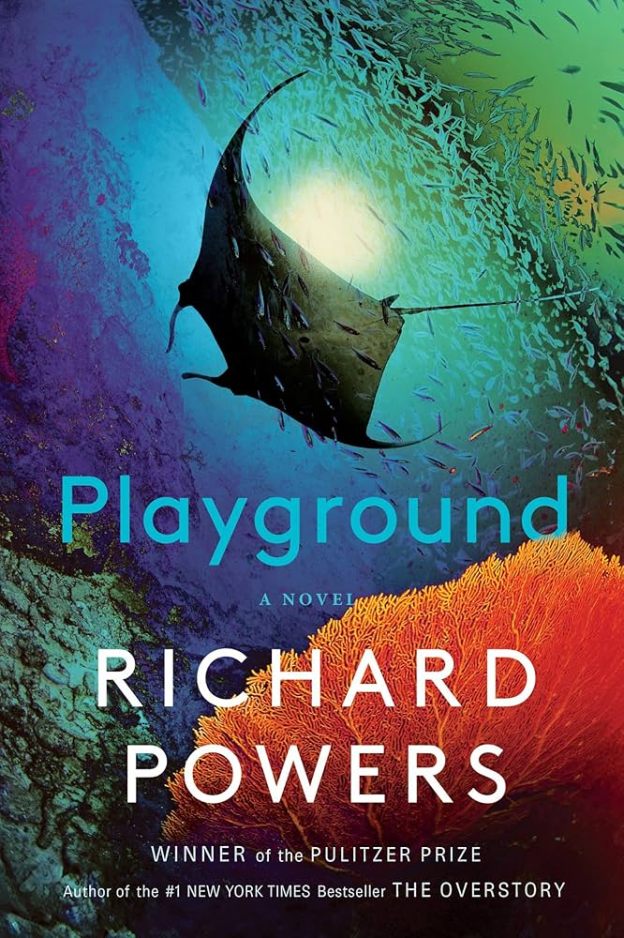

What Richard Powers’ The Overstory (2018) did for the astounding canopy of trees above our heads, Playground does for the super-abundance of seawaters that surround us.

Part letter of appreciation, part eulogy, each novel employs intriguing characters to weave a scrim upon which to embroider an abundance of colorful facts and observations about the environment which gives those characters and all of us life, purpose and – if our eyes are at all open – a measure of sorrow for how carelessly we are diminishing our descendants’ futures.

Where The Overstory was structured around a tale of eco-warriors campaigning to stop forest destruction, here it is Silicon Valley’s takeover of our time and imaginations that drives the plot. Powers braids together the lives of a poet, an explorer, an artist and a social media software tycoon to create both compelling mystery and satisfying conclusion. With thirteen previous novels to his credit, it should be no surprise the product feels mostly effortless and ordained. What does startle though, is how the few moments which do feel effortful – when the wealth of scientific detail seems to veer into pedantry or showing-off – are cast in an entirely different light once it dawns on the reader just who has been narrating the story. Suffice to say that that realization brings into focus yet another level of questions the novel is raising, about memory and knowledge, about fact versus fiction, brain vs. whatever, and about whether the answers to those questions will diminish the stories we read, hear and watch in future eras as greatly as we are currently diminishing our own and only habitat.

(As angry as Powers clearly is about our destruction of species and environment, he is wise enough to include reminders that nature itself will hardly notice our waste. For as many species as we destroy and cry over, natural processes will someday create new ones. Perhaps not as photogenic as the old or perhaps more so – nature has other things to worry about – but either way, new habitats will spring up and new species with them. Long after mankind departs the scene in whatever fashion we do, natural processes will continue creating and embellishing, erring and correcting. Only cosmic forces and events can end that process, and those will operate on their own scales regardless of human activities. It is only we and our descendants who will be injured by our carelessness; to the rest, we are irrelevant – as is whether we find that fact reassuring or insulting.)

Heartfelt, informative, moving and timely; the evidence of this outstanding novel suggests that individual human minds will continue to create entertaining and enlightening stories for many generations to come.

One aspect of our future, at least, to which we can look forward with eagerness.

If you like what you read here or at robinandrew.net, please share any posts as widely as possible – and consider subscribing: it’s totally free!

P. S.: E Unum Pluribus is a new novel that explores multiple themes – language and gender, identity, guilt and even the origins of faith and belief – but speaks loudest in its vision of a post-USA future.

The manuscript is available in six instalments, starting at: