Saw an excellent opinion piece recently about the history of Amendments to the U. S. Constitution, starting with the fact that the document’s authors fully intended it to be revised – the Amendment process is written in, after all (Article V) – and running up through our fifty-plus-year drought of amendments since the 1970’s. It can certainly be argued whether our current divisiveness and the dysfunctionality of Congress are one reason we’ve had no Amendments recently, or one result of that, but the phenomena are certainly related to one another.

Well-thought-through and widely-accepted new Amendments could allow our nation’s founding document to grow and adapt to conditions which have changed dramatically, including: a population which has gone from about four million peeps in 1790 to some 330 million in 2020; a mix of states which has gone from 13 small, young and rural ones to 50 with wildly varied histories, populations and urban/rural characters; multiple technological and cultural revolutions; and an international context the Founders might well struggle to recognize.

Given all that, here are a few modest proposals to be considered when the time seems right

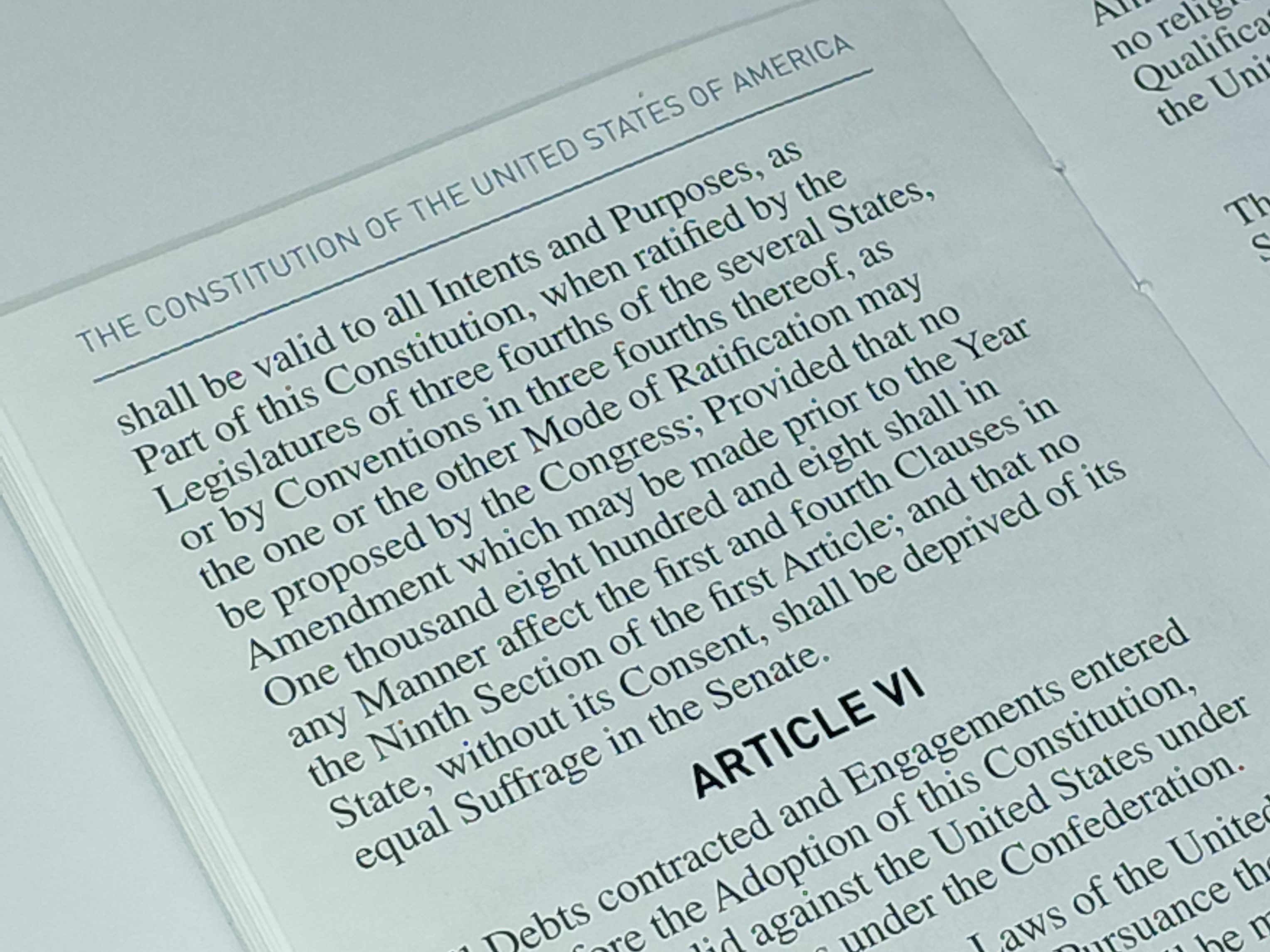

Free the Courts: we’ve all been taught that the Federal government has three branches -the Legislative, the Executive and the Judicial (perhaps equal, perhaps not, depending…) and that this configuration ensures checks and balances on the power of each, thereby protecting the system and our freedoms. Current events are making clear that the Judicial branch is not really an effective check or balance so long as the Chief Executive appoints (even with Legislative approval required) and can fire (at will and whim) the Attorney General, thus allowing that Executive to direct and weild the enormous power of the Department of Justice as he or she wishes. A new Constitutional Convention, or a renewed and less-rigidly divided and more collaborative Congress would do well to consider an Amendment to remedy this by making Justice independent of the Executive branch and the Attorney General an elected office with a four year term, perhaps voted upon in Presidential off-years, and no longer a member of the President’s Cabinet (though still with other rights and privileges of Cabinet level responsibility and authority).

While we’re at it: how about also solidifying the makeup of the Supreme Court by fixing it’s number (rather than leaving it vulnerable to change by some future legislature) and specifying a limited term for justices (so the Court better reflects gradual changes in society and culture) with staggered start dates (so no one President/term gets to appoint more justices than another (whether by random happenstance or by McConnel-esque abuses of Congress’s approval authority). Those changes would work against the politicization some believe we are experiencing with the current Court. And, since we’re talking pie in the sky, maybe even consider requiring each Justice as they take their seat to designate a successor who will fill out the rest of their term should they die, be incapacitated or simply exhausted before it runs out (thus avoiding any lucky President – or violent actor – taking advantage of such an event to pack the court with their preferred jurists).

Speaking of elections: one aggravator of our recent discord has been the ascent of Presidents to office without receiving even the barest majority of the votes cast (not to mention those who did not even receive a plurality!). More than just casting doubt upon a leader’s legitimacy, this has led too many citizens to conclude that their votes are not worth casting. A constitutionally-mandated two-stage election would address this issue, with as many candidates/parties running in the first stage as wish to and then just the two top vote getters participating in a run-off election to decide who will hold the office. That format would ensure the winner receives a majority of votes, while also offering an unmistakable indicator of just how strong or weak is their mandate. It might also diminish the stranglehold of two-party politics, since a third-party or independent candidate need only defeat one of the two major parties to reach the runoff (and have a legitimate chance at the White House), rather than having to surpass both of them from a standing start as under the current system. Whatever expense or delay is incurred by this two-stage process might have ruled it out back in the founders’ days of carriage rides and snail mail but would be entirely manageable in today’s electronic age.

(Debating and reaching agreement on issues like those might even serve as a warm-up so said Congress or Convention could address the stalemate between small and large states with an amendment that retires or at least updates the Electoral College so Presidential Elections would more fairly deal with the enormous disparities in populations relative to Senatorial votes.)

Obviously, tons of other ideas for amendment are out there and more will quickly arise if the ball ever gets rolling, but those above seem to this writer to be top of the list. The time is ripe for us to use the tool those wise heads passed down to us in order that their legacy may be improved and sustained for many more generations!

P. S. – This post was inspired in part by “Amend It!” written by Jill Lepore and appearing in the print and online editions of The Atlantic, October 2025. Neither M. Lepore nor The Atlantic have any connection to this post or site, nor are either in any way responsible for its content.

If you find this post of interest,

please feel free to share it with others.

If you like what you find here at robinandrew.net,

please subscribe – it’s free!